Beyond the cockpit

What can designers learn from aircraft accidents

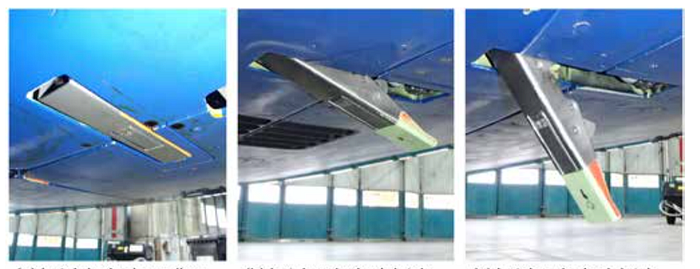

If you looked out of the window on the morning British Airways flight to Oslo on 24th May 2013, you’d see a less than ideal sight.

Shortly after takeoff the outside covers of each engine tore off and ricocheted off the sides of the aircraft. They caused extensive damage to the right engine, fuselage and fuel systems.

After declaring an emergency the plane’s pilot elected to head back to Heathrow.

During their return a ruptured fuel line ignited the right engine.

They shut the engine down, which reduced the fires intensity but didn’t extinguish it.

The aircraft made a hard, but safe landing back at Heathrow.

The plane was evacuated via the emergency slides on the left of the aircraft.

Luckily, there were no serious injuries.

At every stage of this incident, procedures and checklists were followed by the crew. By doing so, they averted a potentially serious accident.

But what caused the engine covers to become unattached in the first place?

When things go wrong in the aviation world, a system is set in motion which is alien to most of us: the air accident investigation.

For months, often years, a team of investigators will comb through evidence to establish exactly what went wrong.

At the end of the process they produce a report. These make fascinating reading.

The report for this incident took 2 years to produce, and runs to 149 pages. I’d encourage anyone who leads projects to read one. They set the standard for open, honest post project reviews and retrospectives.

And best of all, they’re available for us all to read. You can download this incident’s report and read for yourself about the mundane, seemingly unimportant actions which led to an Airbus A319 suffering a major incident.

Or you can let me summarise it for you. Because whilst it does make an interesting read, it’s also full of lessons for us as designers and business owners.

What caused the accident to happen?

Whilst the events of the incident were dramatic, the events which caused it were pretty ordinary.

The previous night, 2 unnamed BA mechanics with a combined 50 years experience were tasked with checking the aircraft’s engine oil levels.

It’s a routine task which forms part of the ‘daily checks’ for an Airbus A319.

The process involves undoing 5 clips which lock the engine coverings closed. These clips run along the bottom of the engine, from front to back.

The covers then swing up on hinges and allow engineers access to the engine.

On that night, the 2 engineers checked the oil levels, much like we do with our cars. They found that both engines needed topping up.

And here’s where things started to go wrong.

Mistake #1: Locking the doors

The oil, and the device which injects it into the engine was stored in a parts store a 15 minute drive away. After the first engineer went to collect them and found an empty shelf, the second engineer drove to another parts store to get the tools.

Here’s mistake number 1. Procedure dictated that the engine covers should either be fully open, or fully locked. The aircraft should never be left unattended with the covers in-between these 2 states.

But this aircraft was left with the engine covers closed, but unlocked. The report says this was a normal thing to do as it saved time for the engineers. No one saw it as a problem.

And it wouldn’t have been, if mistake number 2 hadn’t happened.

Mistake #2: Checking the aircraft

After getting the required parts from the second parts store, both technicians drove back to the aircraft in convoy.

But they didn’t drive back to it. They drove right past it.

Instead of pulling up at G-EUOE, a British Airways Airbus A319, they parked at G-EUXI, a near identical British Airways Airbus A321.

When they got there they found the engine covers locked. They assumed someone else had completed the work, and moved on.

It sounds bizarre doesn’t it, how could 2 experienced engineers drive back to the wrong plane.

We should remember that they were working on the flight line, at Terminal 5. They were surrounded by British Airways painted aircraft and the only distinguishing marks are the registration numbers dotted around the aircraft’s exterior.

It’s an easy mistake to make. The investigation found that technicians tended to navigate to each plane on ‘muscle memory’, without conciouslly checking each plane.

But even this mistake, which the investigators found actually happened quite regularly, would have been recoverable from if it wasn’t for mistake number 3.

Mistake #3: Completing the walk around

Before an aircraft flies the pilot does a walk around. From tiny Cessnas to Fighter aircraft, it’s the same process. The pilot always inspects the exterior of the aircraft for damage and faults.

On this occasion it was the job of the Co-Pilot.

Before a pilot can fly a certain type of aircraft, they have to do a test for it. Just like your car, each model of aircraft is slightly different. Pilots do a course and get a ‘rating’ for each aircraft type they fly.

In the Co-Pilot’s rating for the Airbus A319 he was taught how to do a walk around inspection and what to check for.

He was supposed to check that the engine covers were secure and locked.

He did.

But clearly not very well.

And that was the last opportunity for preventing the dramatic events which were to unfold.

They were all small mistakes which were likely made everyday.

But on that day, they all happened at once.

And what could have prevented each mistake from happening? Checklists.

Why aviation turned to checklists

Humans are fallible. The Aviation world learnt this in 1935 when a prototype bomber aircraft crashed during an Army demonstration flight in Ohio.

Aircraft had become very complicated, very quickly. Pilots could no longer remember every action which they needed to perform to keep the planes in the air.

Designers turned to checklists to help aviators fly safely. At each key stage of flight (engine start, takeoff, landing etc), the pilot read through a list of actions to perform.

It was beautifully simple and it worked. That’s why the aviation industry still uses them today.

Except when they don’t.

There were checklists which, if followed closely, would have prevented every mistake which caused this accident.

Instead, those involved were complacent and overly confident in their own abilities.

And that’s understandable. When you’re smart enough to disassemble a jet engine, or fly an airliner, checking simple stuff like an aircrafts registration number or whether a door is locked is trivial.

But thats exactly why checklists are powerful tools. At the very least they help us prevent mistakes and looking dumb. At most, they save lives.

How we can use checklists

Checklists have a place for us as designers and business people. Here’s how to implement them:

What needs a checklist?

- Not every process needs a checklist. There are a few criteria for tasks which would benefit from one:

- It’s a business critical function which is going to cause more problems if it’s not done correctly AND

- It’s a repetitive tasks which is repeated daily which attracts complacency OR

- It’s an uncommon task which would otherwise require regular refresher training

Which tasks are checklists good for?

Some examples of good tasks which I use checklists for are:

- Onboarding a new client. This requires a few tasks to happen to make sure the client’s details are in our CRM, accounts and communication tools.

- Going to the office. Before I leave the house I run though a packing checklist to make sure I have everything I need. It’s a long way to walk back to pick up my ethernet adaptor.

- Sending designs to developers. If we’re delivering design documentation to build teams (such as annotated wireframes and build assets) we use a checklist to make sure everything is included and all the files are setup correctly.

The reason we have a checklist for all of those tasks is because it stops us creating more work for ourselves, or worse, for someone else.

Remember: “Don’t let the end of your job become the start of someone elses”.

How to write good checklists

Not all checklists are created equally. Here are some tips for making good ones:

- Keep them as a short as possible. In The Checklist Manifesto, Atul Gawande recommends sticking between 5 to 9 items as that’s the limit of working memory.

- Use ‘pause points’ for long checklists. These force people to stop and physically check they’ve done a task, avoiding compliancy.

- Use language which is familiar to your team. Theres no need to write is especially formal language.

- Test your checklists before you release them to your team. The first draft will always fail at some point, so don’t be afraid to iterate.

Further reading:

This post is just a brief summary of a very long, very detailed and very complex report. If you’re interested in learning more, check out these links

Just a little slip: a tragedy of errors for G-EUOE

A great write up of this accident which also inspired me to write this post.

Full AAIB report

The full report into incident, written by the British Air Accident Investigation Branch.

The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande

The bible and definitive guide for checklist lovers.

Thanks to Pieter van Marion for the cover image